In this issue:

- No GMO Salad! GM Non-Mustardy Mustard Greens

- Understanding Neoliberalism

- Bunge-Viterra merger approval highlights myth of competition

- Herd health supports human health

No GMO Salad! GM Non-Mustardy Mustard Greens

Bayer (formerly Monsanto) is getting ready to sell genetically engineered (genetically modified or GM) mustard greens that are gene edited to taste less mustardy. These salad greens could be sold in grocery stores in Canada in early 2025. Bayer also wants to sell the GM seeds to home gardeners and market gardeners.

These genetically modified leafy greens are the first gene-edited vegetable in North America (produced using CRISPR), and only the second genetically modified vegetable grown in Canada (after GM sweet corn). Bayer is testing the market to expand into other gene-edited fruits and vegetables.

Bayer told CBAN that two of the GM greens (Brassica juncea) varieties were in grower trials in the US in 2024 and that growers could start sending produce to US grocery stores soon. Bayer says that these GM greens could reach the Canadian market through these growers, or from Canadian growers, “in the near future”.

These GM greens could be on the market as “mixed leaves, bunched, baby and teen leaf.” They will likely be grown and sold by a few large greens producers under new branding in the US and Canada. It is unlikely that companies will voluntarily label them as genetically engineered.

The GM greens will likely be marketed as salad greens that are more nutritious than lettuce: The spicy mustard flavour was removed from the greens so they could be advertised as “leafy greens that don’t bite back! (a mustard green that eats like a lettuce).”

Bayer also says it is seeking a major home garden supplier to sell GM seeds to home gardeners and market gardeners.

The federal government of Canada recently removed regulation from many gene-edited foods and seeds, and livestock feed. Companies can now also sell these genetically engineered seeds, foods, and feed without telling the government about them.

TAKE ACTION

- If you are going to events such as Seedy Saturday, share CBAN’s information flyer.

- If you are a home gardener, market gardener, or greens producer, make sure you are buying non-GM Brassica juncea seeds and lettuce seeds/salad mixes.

- If you are a consumer who does not grow any vegetables, write to the head office of your grocery store and ask them not to sell any GM greens or other GM vegetables.

The NFU’s position is that all genetically engineered plants, including those developed using gene-editing technology, should be regulated by the federal government. Denying the regulator any ability to assess, review and regulate most new gene-edited plants is irresponsible, and allowing them to be marketed without identifying them as gene- edited is the opposite of transparency. To learn more, visit the NFU’s Gene Edited Seed page at https://www.nfu.ca/learn/save-our-seed/gene- edited-seed/

Visit CBAN’s No GMO Salad page for resources including the information flyer, list of non-GM seed sellers, grocery store contacts and sign-up for campaign updates. https://cban.ca/gmos/products/not-on-the- market/gmo-salad/

Email Fionna Tough at outreach@cban.ca for copies of the info flyer and any information or comments you would like to share.

The NFU is a member of CBAN, the Canadian Biotechnology Action Network.

Understanding Neoliberalism

—by Cathy Holtslander, NFU Director of Research and Policy

he NFU has been fighting for farmers rights, interests and dignity, and opposing corporate control of agriculture for over half a century. We made important gains up until about 1980. Since then, we’ve had a much harder time making headway, and we’ve lost a lot of ground. Our difficulties are part and parcel of the spread of neoliberalism, a set of ideas that undermines people-power and reshapes economies and political frameworks to support corporate power. Understanding it will help us understand our recent history and equip us to face current and future challenges.

Neoliberalism is based on the idea that the “market”, where individuals competitively pursue their private economic interests, is the best mechanism for societal decision-making, and that prices provide all the information individuals need to make decisions. Neoliberalism concludes that the combined result of all market transactions fully expresses the needs and desires of the population. People (at least those with money) thus “vote with their dollars”, making elected governments unnecessary for the most part.

An Austrian academic, Friedrich Hayek first thought up these ideas in the 1930s. Later, Milton Friedman and others at the University of Chicago (known as “the Chicago School”) promoted neoliberalism and encouraged governments to base their policies on it. They test drove neoliberalism in Pinochet’s Chile, then In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Brian Mulroney started using neoliberalism in the USA, UK and Canada. It eventually replaced Keynesianism, the previous approach, where governments actively managed their national economies by trying to balance consumer demand with the country’s productive capacity to prevent another crisis like the 1930s Great Depression.

The shift from Keynesian to neoliberal policy happened during a slow-down of corporate profit rates. Neoliberalism encouraged governments to help corporations increase profit rates by watering down health and environmental regulations, suppressing real wage growth by union-busting, imposing massive interest rate hikes, and removing or reducing tariffs and standards that were said to interfere with growth, trade and the competitiveness of large corporations.

The first phase of neoliberalism involved dismantling Keynesian structures and institutions. In agriculture, the Crow Rate freight rates and the two-price system for wheat ended, single desk hog marketing and the Canadian Wheat Board were dismantled, and agriculture extension services, public utilities and crown corporations were privatized. “Farm” policy became “Agri-Food Sector” policy” as neoliberalism equates the interests of food processors and multinational traders with those of farmers. Ag policy became focused on global competitiveness of agribusiness and increasing exports instead of on farmers’ well-being and farm viability. Predictably, farmer numbers went down, farms became larger and their products less diverse, while agribusiness profits grew.

Next, neoliberalism set up mechanisms to prevent these changes being reversed. In agriculture, the CFIA was set up to oversee regulations – then budget cuts provided a rationale for privatizing many of its functions. Plant Breeders Rights legislation paved the way for seed royalties to fund private public plant breeding. The Red Tape Reduction Act accelerates deregulation. And ongoing tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations reduce government’s ability to regulate for health and safety, create useful programs, or provide needed services. The trade agreements further lock in corporate-friendly policies regardless of which party forms government.

Trade agreements help multinational corporations expand into new markets, allowing them to more easily locate production in low-waged locations with weak environmental laws and to sell in markets with higher- waged consumers, while registering profits in low-tax jurisdictions. With these advantages they displace smaller domestic businesses. Governments in turn compete to attract capital and investment, measuring their own success by how well they serve investors and corporations instead of focusing on the needs and aspirations of their people.

Neoliberal policies further enrich wealthy shareholders and corporations in a vicious circle – the more money they have, the more assets they can buy up and the more money they can make from them. New forms of property – Plant Breeders Rights, Big Data and Carbon Offset Credits – turn what were freely shared commons into new private profit centers. Agriculture- related businesses (inputs, machinery, services, processors) become virtual monopolies, able to remove more and more wealth from the local economy.

Needless to say, this focus on reducing costs and increasing revenues for corporations, cutting taxes and reducing the capacity and role of governments at all levels has an impact on everyday life. By narrowing the focus of policy to matters of competitiveness and growth, neoliberal governments disregard other societal and human values. Quality of life in rural and remote areas is hard hit by neoliberalism. Small, dispersed populations have little power, and low density means rural people must travel long distances, pay more, face bigger risks, or do without many services and amenities. We are seeing the consequences in a weakening social fabric, worsening environmental conditions, growing inequality, and reduced societal capacity to deal with disruptions and crises.

Neoliberalism’s answer is to call on underfunded public services, unpaid care workers, charities, volunteers and community organizations to fill ever-widening gaps.

The political impact of neoliberalism is becoming more apparent. The promised trickle-down of wealth has not occurred. Neoliberal governments equate the public interest with corporate interests, leaving little room for meaningful engagement with citizens. The insecurity, fear, anger and resentment due to economic and political disempowerment is being dangerously amplified and harnessed by right-wing authoritarian populists.

What to do about neoliberalism?

Recognizing neoliberalism as the intensification of colonization and a key driving force of climate change, farmland financialization, and regulatory capture will help us address root causes. Knowing the impacts of neoliberalism helps explain today’s political situation – and can help us build a movement of human beings who take back control from those who would destroy everything in pursuit of money and power.

The NFU cannot confront neoliberalism alone, but we can be leaders by embracing a politics of solidarity; by using, supporting, and defending our commons, public spaces and public institutions; and by demanding that governments use our collective resources to repair the damage done by neoliberalism.

Bunge-Viterra merger approval highlights myth of competition

Canada’s approval of Bunge’s acquisition of Viterra effectively ends competition in Canada’ agriculture commodity sector by giving control of 40% of our grain market to what will become the world’s largest agricultural commodity trader. It is time to abandon the myth of competition and get serious about regulation to protect the public interest. We need a stronger, fully funded Canadian Grain Commission with enhanced authority to protect the interests of farmers.

The NFU and other farm organizations outlined clear harms to Canada’s farmers, which were blatantly disregarded. Both the degree of market power concentration and the specific ways Bunge and Viterra assets are structured will in- crease the merged company’s ability to annually extract hundreds of millions in excess profits from Canadian farmers – and by extension, from our communities and the Canadian economy as a whole.

Canada’s decision puts very light conditions on Bunge. Farm organizations universally opposed the merger. Selling off a few elevators, urging the new company to put some of the higher profits it will make into investments in Canada, keeping its head office in Regina for five years, and putting up a paper firewall between Bunge and the directors it will appoint to G3’s board, will hardly counter the increase in Bunge’s power to influence markets, prices and production within Canada and internationally.

When the merger is finalized, ADM, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis-Dreyfus, will continue to dominate internationally, with Bunge now in first place. Together these four giants control 70% of the world’s grain trade. A 4 firm Concentration Ratio (CR4) above 40% is considered monopolistic. In Canada, the CR4 for grain companies (counting G3 as a de facto Bunge asset) will be 88%.

In her announcement, Transport Minister Anand stated that the merger approval with conditions serves the public interest. Like all corporations, Bunge’s first duty is to its shareholders, and it is certain that its own private interests will guide its decisions. The NFU therefore urges the federal government to ensure the Canadian Grain Commission and other relevant regulators have increased capacity and authority to safeguard farmers’ interests in the face of Bunge’s domina- tion of our grain sector.

For background information and links, visit https://www.nfu.ca/bunge-viterra-merger-approval-highlights-myth- of-competition-and-need-for-effective-regulation-says-nfu/

Herd health supports human health

—by James Hannay, NFU Policy Analyst

In March 2024, U.S. farmers had to come to terms with a Highly Pathogenic Avian Flu (HPAI) mutation that has, at time of writing, spread and infected over 850 dairy cattle herds in 16 states and 70 cases of human infection. Here in Canada, our dairy herds are free of avian flu and the one known human case had no contact with cattle. Why the difference?

Supply Management protects dairy, chicken, turkey, and egg farmers from turbulent market forces. By supporting farmer income through cost of production pricing, Supply Management provides a strong basis for animal health and disease prevention by supporting farmer investment in herd health, with mandatory standardized monitoring and testing of both cattle and milk.

Canada’s supply management system operates on three pillars: production discipline (quota), cost of production pricing and import controls. Distribution of quota among all provinces and between dairy farms means Canadian farms have less concentrated production and more dispersed herds than in the USA. Supply management helps to reduce market risks for farmers by making production more consistent and predictable, without the wide price swings American farmers have to cope with.

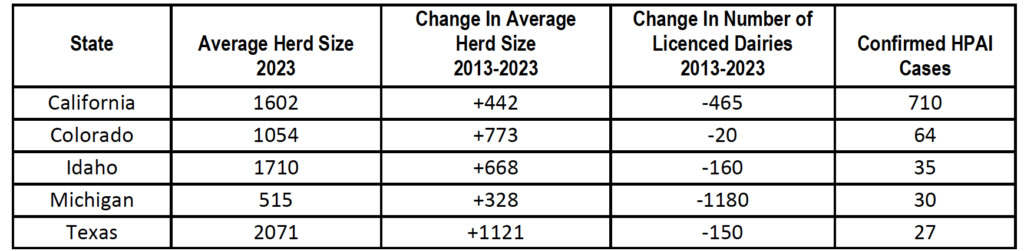

Let us look at herd statistics for the states in the top five of confirmed HPAI cases in dairy cattle:

Source: USDA Economics, Statistics and Market Information System

The data in the table demonstrates the increasing concentration of dairy herds under an unregulated market in the United States. The average Canadian dairy cattle herd size is 96 cows per farm, by contrast.

It is important to note that while herd size and concentration are linked to HPAI outbreaks, they do not cause them; neither does the free-market system for dairy production in the United States. Competition in the free-market system, however, does promote “race-to-the-bottom” business practices, looking to increase net revenue by cutting costs. In many cases this also means cutting corners on herd health and animal care, and even incentivizes hiding HPAI infections to avoid culls. Since farmers are not being paid the full cost of production, successful operations look to increase revenue by increasing output, which leads to even lower prices that force others out, driving consolidation.

There are always losers in competition, and the winners are fewer and ever-larger.

Supply management allows farmers to make a living with smaller herds, and ensure better herd health. By paying fairly for the products, and distributing production amongst more and smaller farms rather than accelerating concentration, supply management creates a more stable market for dairy production.

Supply management, then, promotes herd health by reducing disease risks. It is a good example of the OneHealth approach, which recognizes the health of humans is connected to the health of animals and the environment, and vice versa. Canada’s smaller herd sizes are economically viable and farmers are able to uphold higher animal health standards, and reduce the risk of zoonotic diseases spreading to farm families and farm workers. With Supply Management, we protect our health and our food supply by ensuring farmers are paid properly and by taking animal health seriously.